Making A Book | Ghosts of A Cure

“I just really wanted to write human stories”: Bernice Santos on the precarity of escapism, music as the seed for stories, and drug-fuelled flights from loneliness

In a new series titled “Making A Book”, we delve into the experiences of students who published a book through the course WRI420: Making A Book.

WRI420: Making A Book is an advanced 12-week course in the Professional Writing and Communications (PWC) program at the University of Toronto Mississauga. The course examines principles, procedures and practices in book publishing. Students, working collaboratively, collect material for, design, edit, typeset, print and assemble books. Students consider the philosophical, aesthetic, and economic factors that guide publishing, editing and design decisions. The course culminates in each student publishing a book.

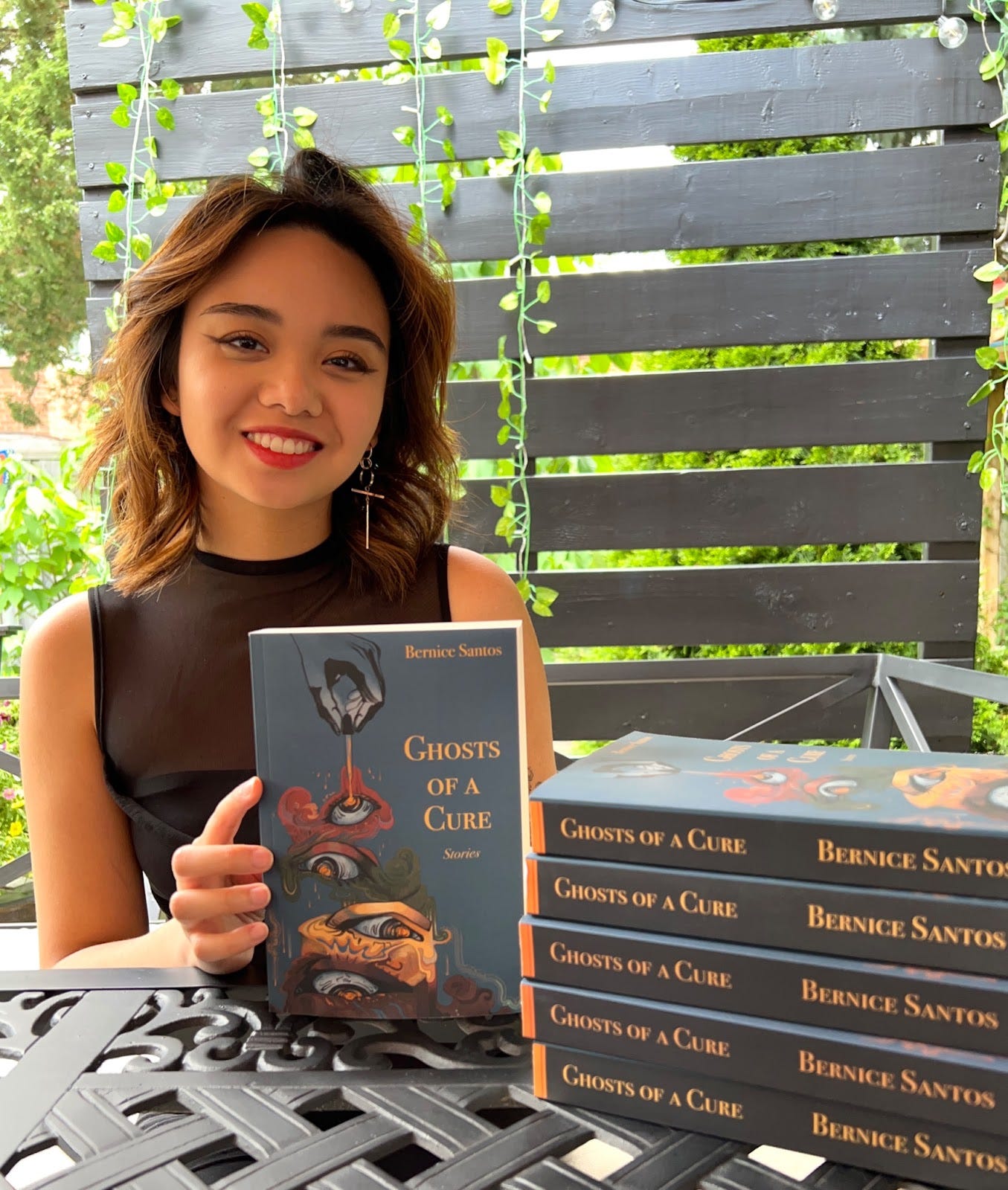

Bernice Santos took WRI420 in the winter semester of 2023 (January—early April). She published her debut collection, Ghosts of A Cure, on April 11, 2023. Three unconnected stories are woven together by Cure, a powerful drug that allows its users to manipulate their own hallucinations. An author suffering from writer’s block brings an unwritten story to life until his characters haunt him into madness. Estranged childhood best friends reunite and conjure hallucinations of their dead loved ones. A pharmacologist experiments with a newly synthesized drug under the supervision of a secret research group. Ghosts of a Cure tells stories of reality and illusion bleeding into one another until they are no longer discernible.

The collection has been named a finalist for the 2023 Whistler Independent Book Awards in the fiction category. The awards, sponsored by the Writers Union of Canada, celebrate excellence in Canadian self-publishing. The winners will be announced on October 13, 2023.

Bernice is a Canadian fiction and non-fiction writer based in Toronto. She holds an HBA from the University of Toronto, where she studied Professional Writing and Communications. She writes short stories, articles, and oral forms of storytelling. Her website is https://www.bernicesantos.com/

W. V. Buluma: Why did you want to make a book? First, why did you want to write a book, and second, why publish it through the course?

Bernice Santos: There were 2 main things that resulted in the idea. The first thing is how I gravitate toward writing about psyche and internal worlds. I think I'm definitely better at that than action-filled plot. And I just really wanted to write human stories that draw on loneliness, dependency, grief, codependent love, and escapism. And I thought that writing through the lens of mind-altering substances would be a really interesting approach because it amplifies and bends reality. So when I coupled that with these very inward themes I gravitated towards, I thought that it would be a really good way to access and write about the internal worlds of these characters.

Which brings me to the second main thing that served as inspiration. I was very interested in the use of psychedelics as a therapeutic tool to treat mental illness and trauma. There's been a resurgence [in psychedelic research to treat mental illness]. I think what a lot of people don't know is that a lot of these psychedelics were originally used as a psychiatric tool in the fifties to seventies during a very fertile research period. These days, these substances are very much associated with the party scene, but they have psychiatric roots from before they leaked out of the clinical setting. I started thinking of characters who might take a similar kind of treatment into their own hands and essentially get addicted to living in a dream state, in which they get stuck while trying to process their trauma.

I really wanted to write a kind of a parallel to the history of these drugs, which were these tightly controlled substances used to make the suffering of patients more bearable that eventually escaped into the hands of people who indulge themselves for different reasons.

And to answer the question of why I wanted to write this book. To put it simply, I just fell in love with the characters that came out and I just couldn't imagine not building a world around them.

Beautifully said. I’m also thinking about the resurgence of MDMA as treatment for severe PTSD.

Just picking up on what you said before, about not having thought about writing the book until a year before you started writing it. In your interview with our campus newspaper The Medium, you said that the collection was “very much a result of the PWC [Professional Writing & Communication] program.” In the acknowledgements section, you thank your editing group and professors in the PWC program. Could you speak a bit more about your development as a writer in your four years of university? If you could speak to your first-year self, what would you want to tell her?

Oh, wow! That's a fun question. If I could talk to my first-year self, I would say that “you were right about falling very deeply in love with writing.” I think that there was a sense of ‘I've come to the right place.’ And I would probably tell her, “you will find the right people. You'll find the right community. And that's all going to lead to something.”

To answer your other question—in these 4 years, I think one of the biggest lessons I learned is that writing is not lonely, or at least it doesn't entail the solitude that a lot of people assume. I remember something that a writing professor told me: “A lot of people think that writing is this romanticized notion of sitting in a dark room by a lamp until it’s finished, but it doesn’t always look like that. It can be collaborative, much more than we’re led to believe. Especially the editorial process.”

There’s a vulnerability that comes with that, especially in the PWC program because of the nature of the things that we write about—it’s very memoir based, very internal. I think because we have the opportunity to share that with classmates in a small program, it really gives us the opportunity to form bonds with people not just as classmates, but as writers and friends.

I’ve certainly experienced that, especially after I took [the year-long course] Editing: Principles and Practice. You spend a lot of time reading other people’s work, revising your own work—you have to be vulnerable and trust your classmates.

That’s actually the course where I met my editing group who encouraged me to write the book.

If you were to create a genealogy of your novel, what would you include? Think of Ghosts of a Cure as a complex, ancient organism—where does it begin to evolve?

The very first thing which everything else bloomed from was Ilah and Jesse [the two protagonists of the second story ”The Runner & The Wallower”]. I think this book is very character-centric, more than action-centric. It's very internal. 90% of the book takes place in these characters' heads, especially in “The Runner and The Wallower.” It was Ilah and Jesse, their relationship to each other and with Cure, that the rest of the book evolved from.

I wasn't just thinking about who these characters all are to each other, but also the world around them. For instance, I took pictures all the time to help myself envision Pergis [the setting of “The Runner & The Wallower”]. Music also helped create their identity. I think I sent you 4 out of maybe 30 playlists. The book wouldn't be what it is without music.

Let’s talk a bit about structure. The middle story you just mentioned, “The Runner & The Wallower” is the longest of the three. The first story, “Pen & Paper Children,” is 74 pages long. The third story, “A Study of Potessomnium,” is 70 pages long, while “The Runner & The Wallower” takes up 256 pages. Why choose to spend the most time with Ilah? Was this the plan from the beginning, or did it evolve more naturally?

I didn't expect it to be the longest. It just happened naturally because that was the story I inhabited the most and it was the first story I ever wrote. When I was putting the 3 stories together, the original plan was actually to have The Runner & The Wallower first. Then I realized that was way too much to hit the reader with from the beginning since this story is the emotional bulk of Ghosts of A Cure.

To answer your question, no, it wasn't always the plan to have it the longest. It just happened because Ilah and Jesse were always at the forefront. They were the ones that as a writer, really helped me shape the identity of the drug and the identity of the book. Everything followed after.

Speaking of that, what was your process for deciding which characteristics Cure would have? You’ve spoken about psychedelics, was there anything else that shaped the nature of the drug?

Researching existing psychedelics was definitely 99% of it, but the aspect of control was what I was really drawn to. [Those who take Cure can control the hallucinations it induces.] Even with existing psychedelics, that doesn't exist. As far as I understand psychedelic-assisted therapy, it's a guided process. But to have that level of complete control over your own mind and to make reality malleable—that's the defining characteristic I had in mind when creating the nature of Cure.

I’m struck by how much your protagonists are driven to addiction by love and loss—for instance, the Author is driven by a longing to see his beloved characters again, and Ilah conjures memories of dead and estranged loved ones. Could you share a bit more about the role loss and grief play in the novel?

At their core, these stories are about different forms of loneliness and the extent that people will go to absolve themselves of it. The book is about trying to find a way out of grief, or out of loneliness, or out of madness, or out of stagnation. It's about the indulgence that comes with escapism, whether it's about revisiting memories before a tragedy or about letting imagination become reality, or about trying to save a loved one by giving them an escape.

I think the point of these stories is exploring that loneliness in different contexts. It's about indulgence. Because it’s human nature to want to satiate that desire, to have control over your own reality.

Considering the length of the collection [400 pages], what was your writing workflow—how did you outline, draft, and edit?

I was writing it for about a year. The kind of writing I was doing in the beginning was passive because I wasn't sitting down at my computer and just hammering out words every day. In the first few months, it was definitely about getting a sense of who these characters were and the world that they inhabit. What that looked like for me was just going out into the world and thinking as the characters. I would think, for example, about Ilah. What does she see when she steps outside of her house? In what ways is Jesse intertwined with her daily life, even after he's gone? I always joke that 80% of the book started out on my notes app, because I was just taking everything down so I could use it later.

The most intense writing happened when there were really no excuses anymore because there were deadlines and they were approaching quickly. That's the point where I really had to sit down every single day, get into that flow, and make sure I didn't let myself break that flow.

I had to work my way around the other courses that I was taking at the time and dedicate every single moment I could [to the collection]. It was very intense. And to anybody who's thinking about taking the course, I definitely do not recommend taking a full course load. One of the first things Guy Allen [the professor who teaches WRI420: Making A Book] will tell you is that this course in itself is equivalent to a full course load. So if you're serious about publishing, then definitely prioritize it over anything else.

“I can’t believe the book even exists sometimes and I feel like it was ghost written when I see my name on the front.”

What surprised you as you went through the publication process? What’s the most valuable thing you took away from this experience?

Time management for sure. There were a lot of times where I thought I wouldn’t make it. On the more technical side, typesetting was a skill set that I had no experience in before. That's something that I walked away from the class with and I hope to keep pursuing it through freelancing opportunities.

But I think the most valuable thing I got out of the course was proof—the evidence that this is something I’m capable of.

What's one thing you learned after publication that you wished you knew before you started?

Marketing is a full-time job. We didn't touch on that much in the class. We focused on everything that led up to the publication, but after publishing, it’s not over. If you're publishing with the intent to bring it out into the world and accumulate as many eyes on it as possible, then it will take a lot of time and effort. It's definitely the non-fun part. Writing is the easy part.

What's your favorite usage of drugs in literature? My favourite is Substance D in Phillip K. Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly.

One of my professors recommended A Scanner Darkly when I was looking for examples of drug writing.

This is a shoutout to my writing professor, Maria Cichosz. She wrote a novel called Cam & Beau. It's not about psychedelics, but she did write a lot about drug use in this book. The way the characters were written with a fog in their heads and the way their emotions were amplified through drug use was really beautifully executed. There is also a sense of obsession throughout the novel. There’s a significant parallel between the drug use and the protagonists’ obsession towards each other.

If Cure existed and you could take it, what do you think you'd conjure?

My characters! When I kept hitting walls while writing, I thought, “this would be such a great time for Cure to exist right now.” But I feel like I might fall into the same trap The Author fell into. [If you’re curious what happens to the Author—read Ghosts of A Cure to find out!] So that's probably not a great idea, and it's probably a good thing that it [Cure] doesn't exist.

Ghosts of A Cure is a finalist for the 2023 Whistler Independent Book Awards (WIBA). Could you share a bit more about your decision to enter your book into the awards, and what being a finalist means to you?

It was actually a very spontaneous decision at 1 a.m. I randomly remembered Shannon Terrell. Shannon is the pride and joy of a few professors in the PWC Program and I remember getting the email from the department last year announcing that she won. [Shannon’s memoir The Guest House: Stories Of A Nervous Mind won the WIBA in 2022 in the non-fiction category.] I remembered that because she published the book through WRI420: Making A Book and this was at a point where I knew I was going to take the course.

I randomly remembered [Shannon’s win], and I just thought, what's the harm? I looked into the guidelines and funny enough, there were 2 days left before the submissions closed. It was just one of those gut feelings of “try anyway, see what happens.” So I submitted my application and the next day, I went to the post office to send a copy of Ghosts of a Cure to WIBA in the mail.

“At the core, these are stories about different forms of loneliness and the extent that people will go to absolve themselves of it. It's about trying to find a way out. It's all about the indulgence that comes with escapism.”

Just to circle back to the second part of the question: what does being a finalist mean to you? If it means anything, it doesn't have to mean anything.

It's unbelievable. It's an honor in every sense of the word. I can’t believe the book even exists sometimes and I feel like it was ghost written when I see my name on the front. So to have it recognized in a really positive way is such an honor. I was up against some really incredible authors and this was open to authors all across Canada. The other nominees have been writing books for decades. I feel like a bit of an underdog, but it's a great honor to be recognized amongst these really talented people. I owe it all to PWC because this book wouldn't exist without this program.

Is there anything else you'd like to add, or an answer you'd like to give to a question that you wish I had asked?

I didn't want to write this as an anti-drug book or as an opposition to the kind of psychiatric treatment [with psychedelics] that's happening right now. I didn’t want to frame Cure as something evil, but instead, as a neutral tool that unfortunately falls into the hands of people who misuse it. At the core, these are stories about different forms of loneliness and the extent that people will go to absolve themselves of it. It's about trying to find a way out. It's all about the indulgence that comes with escapism. Cure just happened to fall quite far from what it was intended to do. Its fate is quite similar to the fate of real psychedelics that escaped the tightly controlled clinical setting in the 50s-70s and became criminalized for many decades.

What are you working on currently or looking forward to working on?

I'm actually writing my second book. It will be another short story collection. This time, it will be human stories told with the aid of non-humans. There's no set date for its release yet, but I'm very excited about it.

Read the rest of the Making A Book series here.

Thank you so much for the feature!!

Congratulations, Bernice! What an excellent interview 💯 I can't wait to read your book, and your new writing project sounds exciting. I'm so happy your great work is being recognized for the masterpiece that it is. There are many, many more achievements ahead!